Sunday, 8 March 2009

Middleton Place

"Today," I was informed, "you'll be visiting Middleton Place. Jan MacDougal will take you there and show you around. She's a docent there and very familiar with the place."

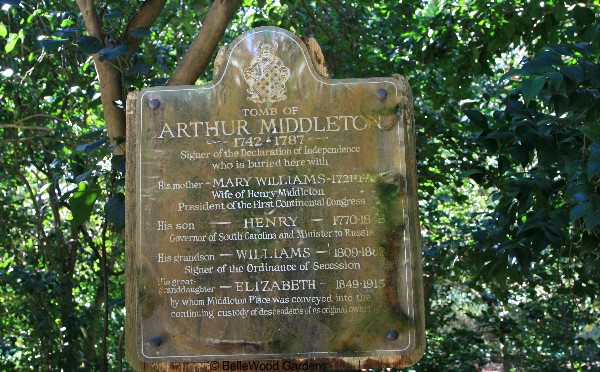

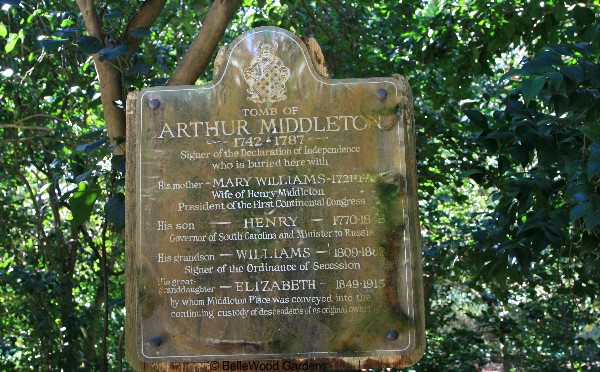

Middleton Place is a National Historic Landmark. A carefully preserved 18th-century plantation, it has survived revolution, Civil War, an earthquake, and hurricanes. Home to several important generations of Middletons, its history begins with in the 18th century with Arthur Middleton, who was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. His son, Henry, was President of the First Continental Congress, Governor of South Carolina, and an American Minister to Russia. And Arthur's grandson, Williams, was a signer of the Ordinance of Secession.

It was Henry Middleton who envisioned the gardens and began their creation in 1741, reflecting the grand classic style that remained in vogue in Europe and England into the early part of the 18th century. Following the principles of André Le Nôtre, the master of architectural garden design who laid out the gardens at the Palace of Versailles, vistas, focal points and surprises were all part of this garden's design.

Great attention was paid to woods and water, geometry, balance, and mathematical, rational order.

Grassy ramps were preferred to steps, creating a more subtle transition,

pleasing to the eye and more convenient for walking. The slope's wide contours

were formed into a series of sweeping, graduated terraces that, steplike, lead

down to the river where a pair of symmetrical butterfly lakes were created.

The site was the dowry of his wife, Mary Williams. Dominated by a high bluff

and sloping down to the Ashley River, the land was worthless for rice cultivation,

which depended on the ebb and flow of tidal rivers to flush the fields. Henry's

original gardens contained allées planted with trees and shrubs, trimmed

to appear as green walls that partition off small galleries, green arbors and

bowling greens. There were ornamental canals designed with mathematical

precision, sundials, minor vistas and statues placed at strategic viewpoints.

In signing the Ordinance of Secession, Williams Middleton endorsed the last Confederate cause.

This failed attempt at independence eventually led to the destruction of Middleton Place.

On February 22, 1865, a detachment of the 56th New York Volunteer Regiment burned

and looted the house and gardens. All that remained was the south dependency building,

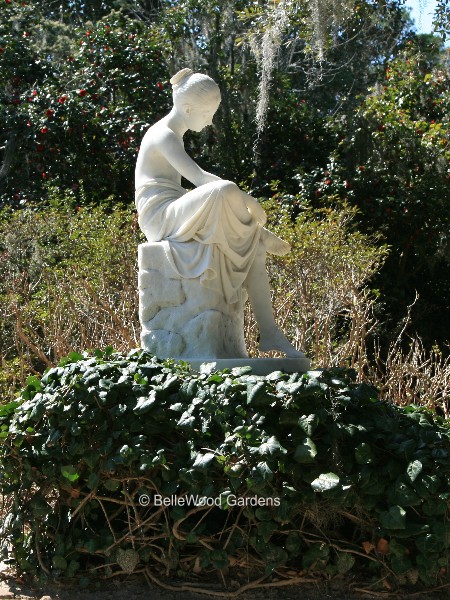

which is today the Middleton Place House Museum. And this statue, which had been buried

and was thus protected from the damage and destruction which befell the house and contents.

Henry Middleton's garden was designed as a superb exercise

in logic and geometry, perfectly adapted to the contours of the land.

Extended vistas in the Carolina Low Country were usually flat, across

wide expanses of river and marsh. Middleton Place was an exception,

standing on high land a quarter of a mile above the river. The water

created an incomparable view as it flowed around the bluff, turning

and forming a wide canal directly in line with the house.

When Henry Middleton started his garden, he was said to own 800 slaves and 10,000 acres.

It took one hundred slaves almost a decade to complete the wide-sweeping terraces, walks,

the artificial lakes and long vistas to the river and marshland beyond. On a visit in 1789

the Duke de la Rochefoucault made mention of the beautiful garden and noted the

"wide, beautiful canal pointing straight to the house."

There are several venerable live oaks, Quercus virginiana, throughout the grounds.

It is, however, camellias for which Middleton Place is noted, both historically and continuing right up to today.

There are more than 2000 camellias including many rare varieties. The Camellia Walk highlights

hundreds of camellias. They form allees in the formal gardens where, at the height of bloom,

tunnels of green foliage are lined with colorful blossoms and pathways are strewn with fallen petals.

There is more than mere quantity that connects Middleton Place with camellias. Middleton family tradition has it that in 1786 the French botanist André Michaux gave the Middletons the first four camellias to be planted in an American garden. Michaux had relocated to Charleston, South Carolina in 1787 after an unsuccessful attempt at establishing a botanic garden in New Jersey. He developed a plant nursery some ten miles outside the city, from where he shipped a great number of North American plants and seeds to France. In return the botanic gardens of France provided him with numerous trees and shrubs that had been collected from all parts of the world. Both from an historical and horticultural point of view, Michaux's Charleston nursery was important in that it was the location where many Old World and Asian plants first arrived in North America, including mimosa or silk tree, Albizia julibrissin; tea olive, Osmanthus fragrans; crape myrtle, Lagerstroemia indica; ginkgo, Ginkgo biloba; Chinese parasol tree, Firmiana simplex; tea, Camellia sinensis; and the camellia, Camellia japonica. The family's oral history holds that the Michaux introduced camellias into South Carolina about a decade before the traditionally recognized introduction by John Stevens of Hoboken, New Jersey in 1797. Since camellias graced the gardens of Englishmen in Jamaica before 1787 (The History of the British West Indies, Edwards, 1793), it is certainly possible that they were brought to South Carolina about the same time. One of the Michaux plants, the Reine des Fleurs (Queen of Flowers) is still extant in the gardens today.

Regardless of when or by whom they were introduced, camellias certainly

have made themselves at home at Middleton Place. in bloom from December

through mid-March, those planted before 1940 form a breathtaking allee

along the border with the greensward. Later plantings are in the new camellia garden.

.

.

.

.

Water is very much a part of Middleton Place. And with water come turtles.

This yellow-eared slider is green with moss, clear indication of the waterways.

Jan was the very best of guides. Knowledgeable, amiable, and well able

to enthusiastically share history, stories, botany, and more. I do hope that some day

she'll get her wish. A journal will be found, in a trunk, in France or somewhere.

And on a page, written in faded ink, will be a diary entry that notes something like

"André Michaux made a generous gift of 4 camellias to Henry Middleton for

his garden. They are the first to be planted in South Carolina." And it will be

an entry for 1786, resolving the issue. For we know beyond doubt that

camellias did come here. It is just a question of when.

Back to March 2009